Illustrations by Kaki Okumura

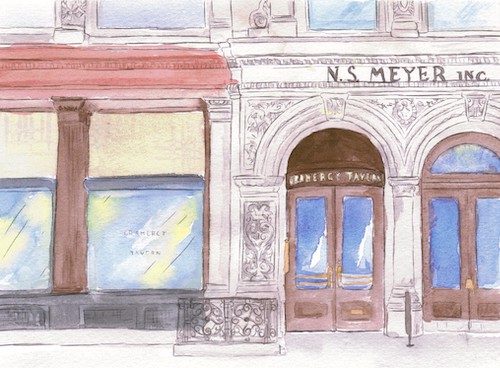

Michael Anthony is the executive chef and partner of the Michelin-starred American restaurant Gramercy Tavern. Established in 1994, it is regularly rated as one of the most popular restaurants in the city and has become a beloved establishment in NYC fine dining.

But what makes Anthony compelling to me is not his long list of professional accolades, but that he speaks like a dad — with an eagerness and excitement to share his knowledge with everyone. He is known for his philanthropic work: He is an active board member of NYC-based nonprofit God’s Love We Deliver, and, through his restaurant, connects with local schools to teach about the joy of eating healthy and locally produced foods.

For a chef so closely defined by his work in contemporary American cuisine, it was surprising to me when I discovered that Anthony spent his early years training in Tokyo. When I got the chance to ask him some questions, it was fascinating to understand how his time in Japan shaped his professional philosophy.

KO: French and Japanese cuisine are both popular cuisines, and you studied in both countries, but when you first arrived in New York, you decided to do American food. Why was that, and how has that shaped how you define contemporary American food?

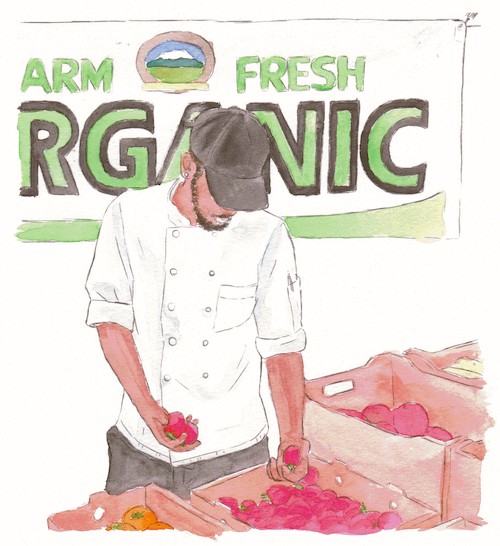

MA: When I’m in Japan and I talk about American food, most people just look at me and they don’t know what I’m talking about. Our mainstream culture is built to ignore the changing seasons and to standardize sourcing so that you could have oranges and tomatoes everywhere, whenever you want them. But when I start to talk about the resurgence of local agriculture, it provokes an inspired return to environmental roots. If we take a look at what’s happened in the last 20 years, there’s a counter-culture movement in the U.S. of learning to ask good questions: Where is this from? How is it produced? Who is responsible for it? How did it make its way to our kitchen or our table? Where can we buy more of this and how can we ask more questions? I know it can be a pain in the butt to provide meals for yourself and your family, but it doesn’t always have to be a burden. It can be a joy. So somewhere buried in all of this, I find — both from a home cook’s perspective and a professional chef’s perspective — a lot of fascination with changing American dining.

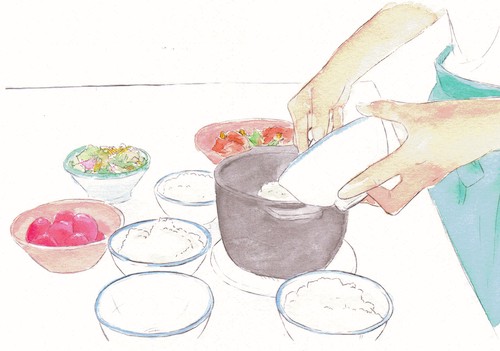

To backtrack a bit, like a lot of college kids, I graduated from university and then moved to Japan, and I got a job working for a language school. In my first six or eight months, as I started to get to know my students and their families, a couple of them invited me into their homes. You know how a lot of middle-aged Japanese mothers have clubs where they study cooking or film? I was like the mascot in my little suburban literary club where their interests were studying English, hiking, poetry, and French films — many things that I loved. I said that I would participate if they would share with me how they cook at home. So each Friday morning, I would go to one of the member’s homes and they would show me two or three dishes they would cook for their family. Very simple, common dishes. But what really impressed me was not the overall refinement of the cooking, but the sense of healthiness and care that went into these average meals. To this day, the invention and the source of inspiration for the creations we serve at Gramercy Tavern comes mostly from the idealism of the way we should cook at home. When I say we, I mean everyone. It comes from the lovingness and the wholesomeness and the generosity and the healthiness of home cooking.

I want to talk a bit about your first mentor, Shizuyo Shima. What kind of person is she and how has she influenced the way you see good leadership in a kitchen?

Haha, sensei wa kibishikatta yo (translation: she was very strict). I was living in Japan and trying to make sense of where I was and what was happening. I was interested in food and I had lived in France before that and had a little bit of knowledge to work with.

While I was far from home and trying to explore the world, I decided that I would reach out to a writer at the International Herald Tribune — an American guy named Clint Hall. I had never met him. I just read [his food columns] and he was kind enough to answer me, unbelievably. I told him that I was interested in going to the Tsuji Culinary Institute in Osaka, and in order to do that, I needed professional experience working in Japan. I asked him kind of generally, could he imagine that any Japanese chef would allow me into their kitchen to get that experience? And he met with me and had suggestions.

What? Wow.

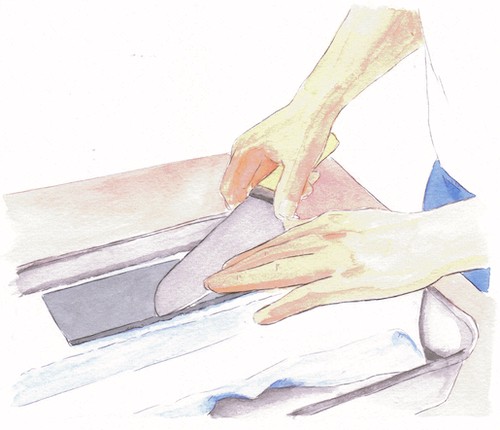

Yes, and he introduced me to Shima-san. She would yell at me and was very stern, but it was also unconditional. I don’t know if I would call it love, but it was an unconditional relationship. I think about my first year and a half working with her, every day of my professional life. I learned all of the basics in that first year: A smart chef is always thinking ahead. A good cook chooses the right tool for the right job. The kitchen is always immaculately clean or else the food won’t taste right. All these very basic things I learned right away. Not only did she teach me about working in a kitchen, but she helped me understand the nature of the relationship between chef and student, and how I would develop my own relationships with the people who work for me. That has been what I consider to be one of my strengths, and it started from my very first experience working with her.

Has having your own daughters and having your own family changed the way you view the role of food in our daily lives?

It’s a bit cliche, but becoming a father definitely brings on the notion of, how do we eat healthy? How do we enjoy eating and make that a part of our everyday lives? But how do we pay close attention to this notion that eating well should be eating healthy at the same time? I can’t force my daughters to eat well, but what I want them to have is a treasure chest of stories, of techniques, of understanding, and tools that they’ll use to build their own lives. It’s related to the social responsibility that I think every business has, but especially being a chef, we’re built for our communities and we have to offer them more than just good food and drink, or a nice place to meet. I see my job as it belongs under the umbrella of education, and it’s what makes me excited and what I think makes people want to work in my kitchen.

My final question: Do you have a favorite memory from when you were still starting out in Japan?

There are many and I’ll tell you about one of them. It was the beginning of August and it was starting to get really hot and muggy in the Tokyo area. I was invited to a small picnic to watch fireworks along the banks of the river, and we sat in this kind of tall, grassy area, where it felt like there was a blanket of heat rolling down on top of us. It was quaint, a very simple setup with just some common Japanese foods, but the cold foods we had packed into our little bento boxes tasted so good in that heat.

And as we sat eating our food and watching the fireworks, the thing that resonated with me is how traditional Japanese fireworks are very different from those in the States. In the States, it’s that the more the better — the louder, the more colors, all at once. But I was sitting in this moment along the bank looking up at the black sky thinking, where are the fireworks? Then one would go up, and it would explode, and it would kind of drift into nothingness. Then there was a long wait, and I would eat some food, and then one more shoot up and we would watch it until it disappeared. I’ll admit I was a little sarcastic at the moment, thinking this isn’t really so spectacular. But I came to realize that the aesthetic aim was different. It was almost the negative image that was to be more powerful than the actual explosion, and the attentiveness to those quiet moments is what makes life in Japan different.

Another distinct memory I have is through one of my students at the language school. She was an older woman, and at the age of 75, she had decided to take language lessons. One summer day she invited me to visit her home and meet her husband, and he introduced me to the game called Go. It was kind of funny, as an American college kid from the Midwest to be sitting on a porch in a yukata, intently staring at this game board trying to strategize. I was not good at it and he would demolish me, but through the game, he introduced me to eating somen noodles in a cold bowl with an ice cube, and drinking homemade umeshu. They were just friendly people that invited me into their home.

Those memories of learning the few foundational aspects of Japanese life, and having those be connected to those cool summer foods, was really influential. These experiences made me realize that our most powerful memories come from a context, and most frequently that context is packaged within a season, and that season is associated with a specific place and people who share ideas with you. So when you can make sure that the food is appropriately connected to a context, it becomes long-lasting.

When I think about making dishes and menus at Gramercy Tavern or wherever I cook today, I’m always thinking about them within the context of the moment. I’m sure that these are universal lessons and they’re true wherever you go — I was just lucky because they happened in Japan for me.

If you enjoyed this piece, let me know at kokumura@kakikata.space! I welcome comments and questions, and look forward to hearing from you 😊 Warm regards, Kaki